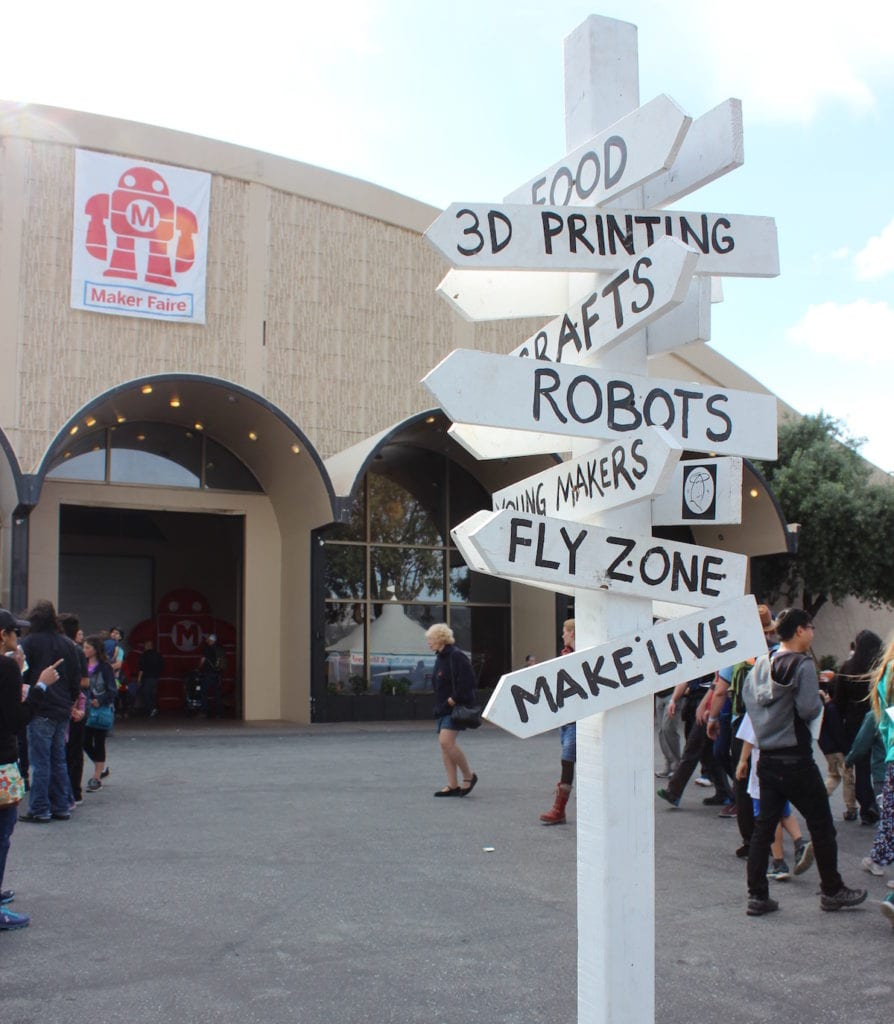

Steam-Powered Tinkering

Troye Welch, the president of Kinetic Steam Works, explains his steam-powered kinetic contraption to Maker Faire attendees.

Toward the back entrance of Maker Faire, an elaborate contraption with pipes, pistons and a boiler pumped a plume of white steam into the air. Standing proudly before it was Troye Welch, the president of the steam-powered kinetic art collective Kinetic Steam Works and a field service engineer by day at Siemens Healthcare. Welch oversaw his near disaster. “We never got it to work until yesterday,” he boasted. “You don’t learn anything if it works perfectly the first time. The troubleshooting is where the learning happens.”

A young observer watches steam-powered kinetic devices at work.

Using kinetic energy and steam, the machine demonstrates the properties of refrigeration, chemical reactions, and mechanical energy. The Rube Goldberg device converts energy into multiple forms and loses it along the way to ultimately produce a bucket of ice-cold water — all in the name of experimentation.

Welch dips a tube of Gatorade into the bucket of ice-cold water, causing it to form ice crystals.

“If you make it fun and tactile, that’s when people absorb it,” Welch said. “If you make it interesting, then people can’t help but learn.”

Welch lamented that when he was in high school, smart kids were a target for dork jokes. “In other countries, being smart is cool! We need to change that. We have to make being smart socially acceptable. Events like this push us in that direction.”

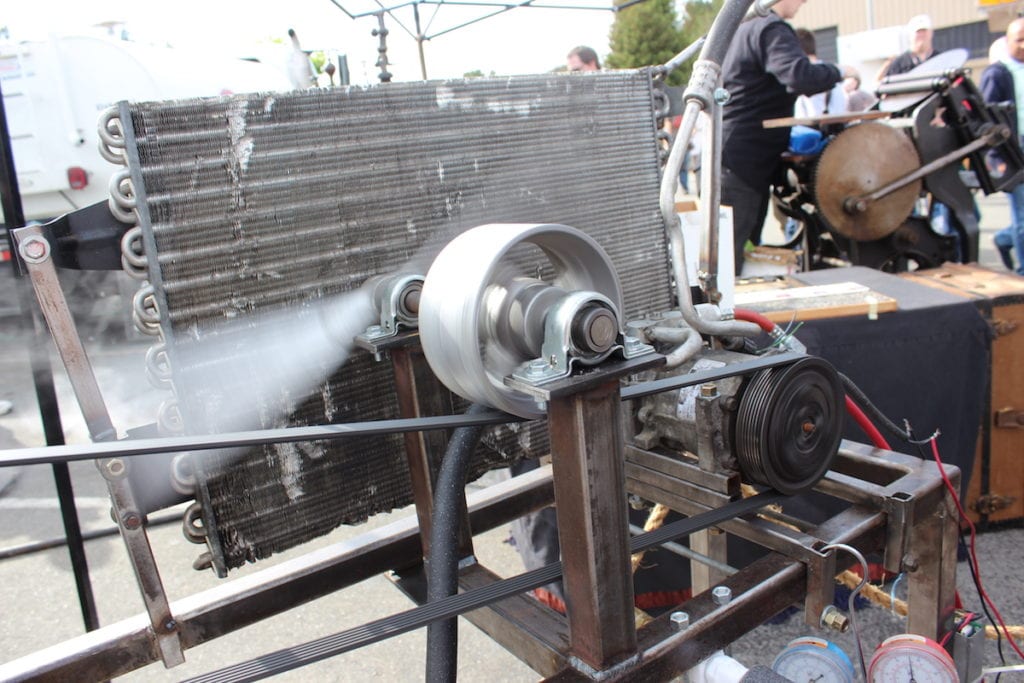

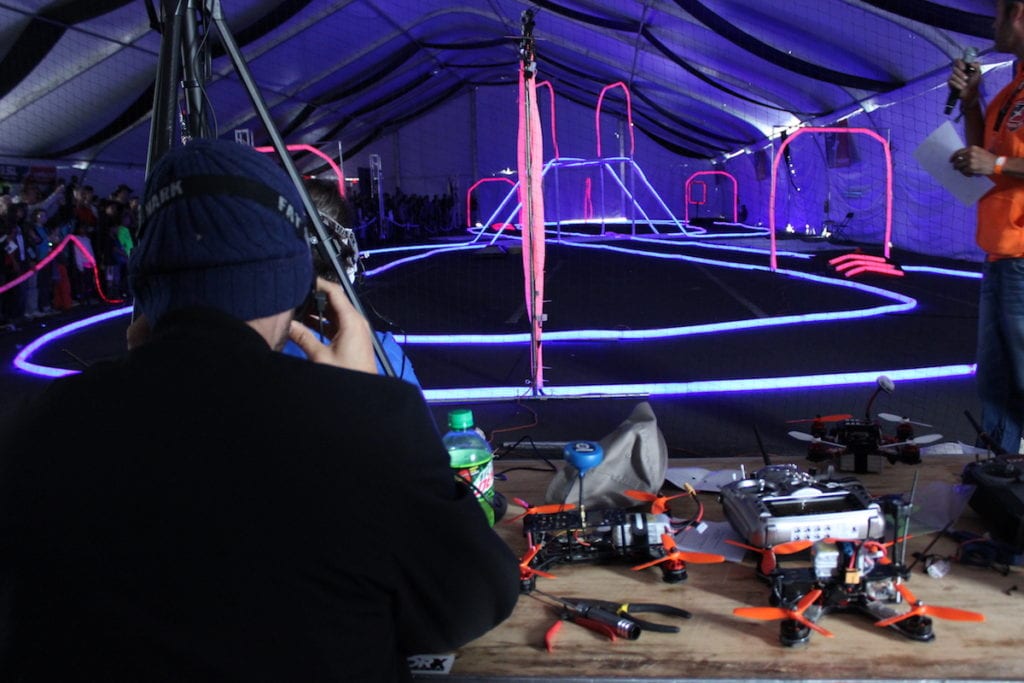

Drone Pod Damage Control

Drew Price, a contract scientist with NASA and a hobbyist drone racer, examines his pod after five rounds of races.

In a dark tent, hand-built drone pods with neon lights zipped and zoomed through the air like high-tech fireflies. Just outside, Drew Price, a contract scientist with NASA, nursed his newly repaired drone. His aircraft had crashed in the first round. “I was so disappointed,” Price said of the first round. “You try to relax and breathe and refocus.” The prop was bent, so he spun it around to get it back on track. Price went on to win four rounds, hanging on in 14th place overall.

A red drone whizzes past the neon race track.

“I’ve done a lot of races, and you always have the jitters,” Price explained. The Maker Faire race required more strategy than usual because it involved points and a bonus gate that drivers could squeeze through for a boost to their score, he said. “It’s risky, so you weigh the pros and cons.”

Price gears up for his sixth round of racing using his first-person view (FPV) goggles.

On his sixth round of racing, Price made a few perfect laps. Then, he decided to go for the gambit: threading through the narrow bonus gate with his several-inch-wide drone pod. It smacked against one of the railings and landed upside down on the floor. Price took off his racing visor and shook his head. “I regret deciding to go for the bonus gate,” he said. Next race, he committed to practicing the track more before the big day.

Price said he enjoys fixing a broken drone, a common setback of the sport. “We all joke around that if we don’t break a pod, we don’t know what to do with ourselves. … There’s the satisfaction of completing something, and getting new parts is always fun.”

Luminous Artists

Cool Neon’s Litewall, made of programmed LED lights.

In the middle of a dark exposition room, a wall of vibrant, programmable LED lights rippled patterns such as diamonds and waves. The mastermind behind the Litewall, Benjamin James, stumbled into his business, Cool Neon, by coincidence. An electronics tinkerer, James saw something astonishing at Burning Man in the late nineties. A bicycle looked like a horse galloping through the desert, made possible with programmable lights. “It was the rave of Burning Man,” he remembered.

Maker Faire crowds admire the glow of Cool Neon’s booth.

James knew he wanted more of this technology. But then he discovered that electro-luminous (EL) wire wasn’t available for purchase in the United States. “I was obsessed,” he said. So, naturally, he bought thousands of dollars of the EL wire from Israel. James hoped to break even by selling it to artists at the next year’s Burning Man. “I thought, ‘So what if I lose a few thousand dollars?'” he said. “I didn’t end up losing a penny.” Since then, a business was born at the intersection of arts and electronics.

Benjamin James stands behind his Cool Neon booth, backlit by electro-luminous wires and LED lights.

Pop diva Katy Perry has worn Cool Neon’s electro-luminous wire on the “Late Show with David Letterman,” in the form of peacock feathers programmed to the beat of her music. Singer Ariana Grande has worn its double-density LED light roll as dress trim. “I just get so strung out on the feedback,” James said. “People say, ‘Look what I was able to do because of you!'”

3-D Printed Possibilities

Researcher Dylan Brenneis waves hello with the 3-D printed prosthetic arm he created.

As a graduate researcher in mechanical engineering, Dylan Brenneis often gets tired of staring at the computer. That’s why he was amped up when he was able to contribute to the construction of a 3-D printed, machine-learning prosthetic arm. He helped build it not only using his coding skills, but also his own hands.

“One of the most memorable moments was seeing the fingers twitch for the first time — I did something that worked!” he remembered. “Building with your hands is remarkable. I want to be an inventor when I grow up, ” he said with a laugh.

The prosthetic arm uses machine learning to make decisions and predictions on its own to move fluidly, freeing the wearer from having to make every small choice and input. This summer, BLINC Lab — his research group at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada — plans to release open-source software to share the prosthetic with anyone. The group released the hardware for the arm’s construction during Maker Faire weekend.

Whenever he gets stumped trying to fix a broken part, Brenneis tries to view it as a challenge instead of a problem. “I step back and think: What’s my overall goal here? It’s to get the fingers moving. So I find a different way to do that. I find it more fun than frustrating.”

Images via Rebecca Huval

Share this: